By Matt Walters – @matthew_walters – matt.walters@decipher.co.uk

How we groaned. And, days on, how we continue to. The morning that followed a tumultuous day before – the day that had seen the industry react to the BBC Trust’s backing for the closure of BBC Three, banishing the channel to an uncertain online-only future – began ordinarily enough, with the publication of the conclusions of Ofcom’s Third Public Service Broadcasting Review. The final document – if not headline-grabbing – brought to the surface the significant contribution made by the PSBs, and yet was cognisant of the challenges ahead facing them. Then something odd happened. And it’s led us to the view that July – though only thirteen days old – has not been the proudest month for the UK’s TV journalism community. Permit me to explain.

How we groaned. And, days on, how we continue to. The morning that followed a tumultuous day before – the day that had seen the industry react to the BBC Trust’s backing for the closure of BBC Three, banishing the channel to an uncertain online-only future – began ordinarily enough, with the publication of the conclusions of Ofcom’s Third Public Service Broadcasting Review. The final document – if not headline-grabbing – brought to the surface the significant contribution made by the PSBs, and yet was cognisant of the challenges ahead facing them. Then something odd happened. And it’s led us to the view that July – though only thirteen days old – has not been the proudest month for the UK’s TV journalism community. Permit me to explain.

The press commentary that followed the Ofcom report was excitable, alarmist even, but it wasn’t the report’s sweeping themes that had got those who cover our industry excited. It was a single line that explained the current state of play in 16-24s’ relationship with live broadcast television. First out of the blocks was the Financial Times, in an article (thankfully since corrected), that authoritatively claimed that “only half of 16-24s watch live TV amid fierce competition from online streaming services such as Netflix”. This was followed shortly after by an article in The Times, which made the same claim. Before long, a casual online search would bring up dozens of publications, print and online, making the same assertion. Regrettably, it was even to found in some of the following morning’s editorials (see Exhibit A from The Telegraph, which at the time of writing remains uncorrected).

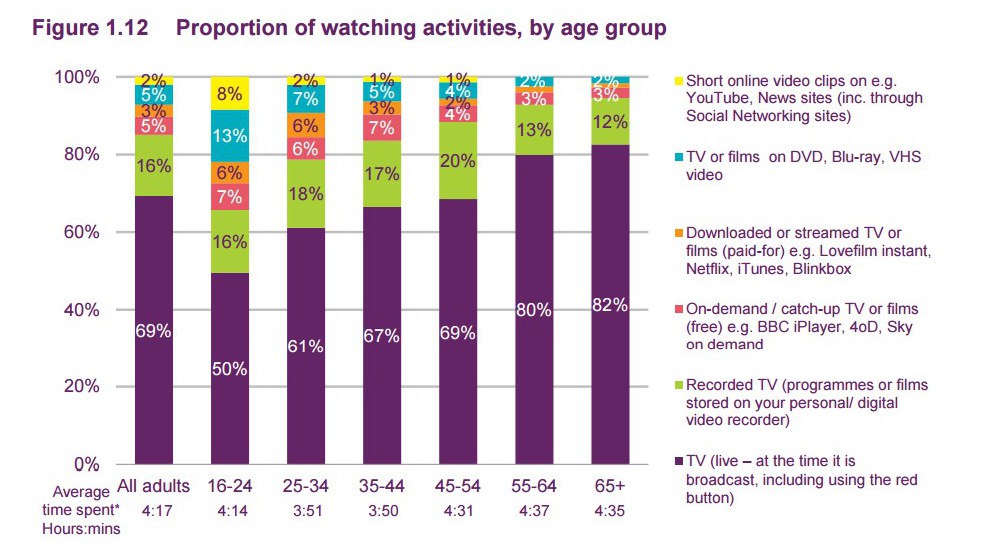

Sceptical and undeterred, we traced the claim, reported as fact, back to its source. It was an insight from Ofcom’s 2014 Digital Day research (see left) that among 16-24s – as a proportion of their total viewing – 50% is directed to live TV. Our uneasy sense of something just not being quite right had borne fruit. Ofcom’s research had, crucially, demonstrated an entirely different point. Not only is 50% of UK 16-24s’ total viewing directed to live TV, if you included PVR’d viewing (16%) and online catch-up (7%) – both TV-centred, though timeshifted, activities – this rose to 73% of total viewing. Fleet Street’s finest were not only wrong, but they’d copied each other parrot-fashion in a manner all too commonplace in the age of the 24-hour news cycle. It later emerged a Press Association newswire had perhaps made the original claim. Such inaccuracy is not only bad for journalists’ credibility but casts dangerous, frankly unnecessary, shadows over the UK’s television industry – an industry, if only the value of the UK TV advertising market is taken into account, that will in all likelihood exceed £5bn in 2015.

Sceptical and undeterred, we traced the claim, reported as fact, back to its source. It was an insight from Ofcom’s 2014 Digital Day research (see left) that among 16-24s – as a proportion of their total viewing – 50% is directed to live TV. Our uneasy sense of something just not being quite right had borne fruit. Ofcom’s research had, crucially, demonstrated an entirely different point. Not only is 50% of UK 16-24s’ total viewing directed to live TV, if you included PVR’d viewing (16%) and online catch-up (7%) – both TV-centred, though timeshifted, activities – this rose to 73% of total viewing. Fleet Street’s finest were not only wrong, but they’d copied each other parrot-fashion in a manner all too commonplace in the age of the 24-hour news cycle. It later emerged a Press Association newswire had perhaps made the original claim. Such inaccuracy is not only bad for journalists’ credibility but casts dangerous, frankly unnecessary, shadows over the UK’s television industry – an industry, if only the value of the UK TV advertising market is taken into account, that will in all likelihood exceed £5bn in 2015.

We don’t raise these glaring mistakes to poke fun at others’ misfortune, but more to seize the chance to restore some sense to discussions on perhaps one of the television industry’s biggest, if not its most intriguing, challenges. Sensible debates about the evolution of television and broadcasting, and the place of television in the lives of this particular age group, just cannot take place when the terrain under the microscope is so fundamentally misreported and, perhaps as a consequence, misunderstood. What follows is our attempt to set the record straight, based upon the latest research and thinking available to the industry. These are the five ‘facts’ that we need to keep ramming home:

FACT 1 – As a proportion of total average daily video time, live TV accounts for roughly half of UK 16-24s’ video consumption

Recent research from Thinkbox (see right) has provided the most up-to-date and revealing window on how 16-24s are spending their video time each day, and how this compares to the population at large (see chart, right). Perhaps unsurprisingly, while the general population spends on average 4 hours and 20 minutes consuming video each day, 16-24s consume less (3 hours and 30 minutes on average). Some of this is the obvious shows. For example 4.6m (69%) of 16-24s watched the most recent series of The X Factor (2014) and over 4m (62%) of 16-24s watched the most recent series of Britain’s Got Talent (2015). But some of this is still traditional, less obviously ‘youth’ shows – for instance over 1m 16-24s tune in to watch Coronation Street every week.

Recent research from Thinkbox (see right) has provided the most up-to-date and revealing window on how 16-24s are spending their video time each day, and how this compares to the population at large (see chart, right). Perhaps unsurprisingly, while the general population spends on average 4 hours and 20 minutes consuming video each day, 16-24s consume less (3 hours and 30 minutes on average). Some of this is the obvious shows. For example 4.6m (69%) of 16-24s watched the most recent series of The X Factor (2014) and over 4m (62%) of 16-24s watched the most recent series of Britain’s Got Talent (2015). But some of this is still traditional, less obviously ‘youth’ shows – for instance over 1m 16-24s tune in to watch Coronation Street every week.

It is true that live channel viewing amongst 16-24s is less that the general population. But this has always been the case. Whereas 67% of the general population’s average video time per day is directed towards live TV, 49% of 16-24s’ average video time each day is towards live TV. However, when adding in playback TV (i.e. PVR’d content – 9%) and broadcaster VOD (7%), the proportion of television-related activity among 16-24s still rises to 65% of their total average video time per day – far outweighing YouTube (7%), online “adult” video (7%), and subscription VOD (4%).

When set in the context of 16-24s watching 70% of their video via the TV set, and television itself reaching 87% of 16-24s each and every week, this evidence makes very light work of the sensational claims of one Rick Gibson – in a piece published in The MediaBriefing on Friday – that there is a “very real daily war being fought between YouTube and broadcast TV for the viewer’s attention”. It’s simply not the case. Television remains a substantial, indeed the biggest slice, of the video pie, both for the 16-24s and for the general population at large and for 16-24s the video watching pie is big and continues to grow.

FACT 2 – Watching broadcast television, as a claimed monthly activity, has remained unchanged amongst 16-24s over the last twelve months in the UK

According to Decipher’s Mediabug research, over the last two waves – or twelve months – watching broadcast TV has remain unchanged among 16-24s, as a claimed monthly activity, with 86% tuning in at least once monthly. This is admittedly lower than the 25-34s (89%), the 35-44s (88%), the 45-54s (92%), and those aged 55+ (88%). That said, we aren’t seeing among 16-24s the flight from broadcast television, and the consumption of television content, that’s being reported in the press. Small, subtle differences in behaviour (see below), yes, but across all age groups live broadcast remains the most frequently used way to consume television content.

FACT 3 – There are subtle differences in how 16-24s consume non-live forms of television content, relative to other age groups

Another revealing insight coming out of our Mediabug research is in how 16-24s consume non-live television content. Again as a claimed monthly activity, both the 16-24s (79%) and 25-34s (74%) prefer use of online catch-up services (for example, the online versions of BBC iPlayer and All4) to recorded (PVR’d) television, preferred by the older age groups. PVR use is most frequent among 25-34s. Use of catch-up TV VOD services (for example, the catch-up provided via platform set-top boxes by the BBC and ITV), is actually a more frequent activity among 25-34s (52%) and 35-44s (51%) than it is among 16-24s (49%). Though there have been small shifts in the associated percentages, this hierarchy of behaviours has remain unchanged over the last twelve months.

FACT 4 – There are important (and subtle) social and cultural factors at work that determine how much television and video 16-24s consume, and how and why they consume it

Returning to Thinkbox’s recent research, the body’s work with Platypus Research recently shed important light on often overlooked, interlinked social and cultural factors which shape and influence 16-24s’ television and wider video consumption.

The first is “time and space”. 14-24s have more free time than the rest of the population, and so have a broader spectrum of video-viewing – ranging from highly immersive viewing (for example, television drama) to boredom-busting. Television plays an important role across the piece, as do SVOD services such as Netflix for some. Online video services such as YouTube are considered closer to the “boredom-busting” end of the spectrum than truly “immersive viewing”. Notably, this age group is often constrained in terms of access and control to the main television screen (either at home with parents, or with friends/siblings in shared accommodation), explaining why 16-24s are more likely to watch video on devices such as tablets and smartphones.

The second is “identity”. The period between 14 and 24 years of age is a formative one in terms of identity, and those within this bracket are keen to connect with people of a similar age (to whom they can relate, and from whom they can take guidance). The emergence of vlogging has, to some degree, helped to satisfy this need. Short-form video content serves a desire to learn among this age group well, but so too does television – at a more aspirational and directional level. One anecdotal example from the research was the ability of Channel 4’s One Born Every Minute to drive applications for midwifery courses.

The third and final factor is “social maintenance”. Television plays a very important role in maintaining and enhancing physical social maintenance, bringing friends and families together, and allowing people to find points of commonality. Indeed, ITV’s Primal Screen study found that 80% of 16-24s viewed television as the number one medium for bringing families together.

Virtual social maintenance, a newer phenomenon accelerated by the rise of social media, sees many 14-24s seek to be active in the virtual world to maintain the persona they want to portray. Short-form video plays an important role here, as it is “traded” and shared (almost as currency) between friends. So too is television important in this respect. Social media allows for 14-24s to virtually share the experience of watching a favourite television programme as a form of social “badging” and self-expression. The effect of this, when viewed in the context of a series like ITV’s The X Factor (the most recent series of which was viewed by 4.6m, or 69%, of 16-24s), is considerable. Often lost amongst today’s press commentary are simple truths such as over 1m 16-24s tuning in to watch Coronation Street each and every week.

FACT 5 – The UK and the US markets are fundamentally different. There is no easy “read across” between the two

On these very pages back in February, our own Nigel Walley made a robust case for how the UK and US television markets differ, and why this matters. It is unwise, yet all too easy and all too tempting, for commentators to say with certainty that because 16-24s in the United States consume television or video more widely in a particular way that this will definitely become a reality in the UK. Evidence of this, for better or (most likely) for worse, surrounds us. One unfortunate, if comically titled, article in Friday’s Times (“iPad Generation Told to Watch TV as Punishment”) casually suggested that, though the survey under discussion was conducted among parents in the United States, “British families are likely to be heading in a similar direction”.

Unfortunately, perhaps predictably, even in the writing of this piece, the industry’s more wayward talking heads have been having their say, even despite the evidence provided above to the contrary (see “Death of the TV: Why We’re All Streaming Now” from Friday’s Times). What can’t be denied in all of this is that the 16-24s, and those just a few years younger, present the television industry with searching immediate and longer-term questions, even if the current reality is far less stark – dare I say it, more positive – than many doomsayers make out. Young viewers have historically always been a difficult crowd for television to please and to retain, and cementing both satisfaction and loyalty in this ever more converging environment of alternative services, alternative devices, and alternative distribution methods will be of the utmost importance. The question of whether newer, evolving consumption habits will “stick” as our 16-24s move through their adult lives (and to what degree) remains one of television’s great unanswered questions. Until we find out, the least we can do for both the industry and for ourselves is choose our words a little more carefully.